Friday, 26 July 2024

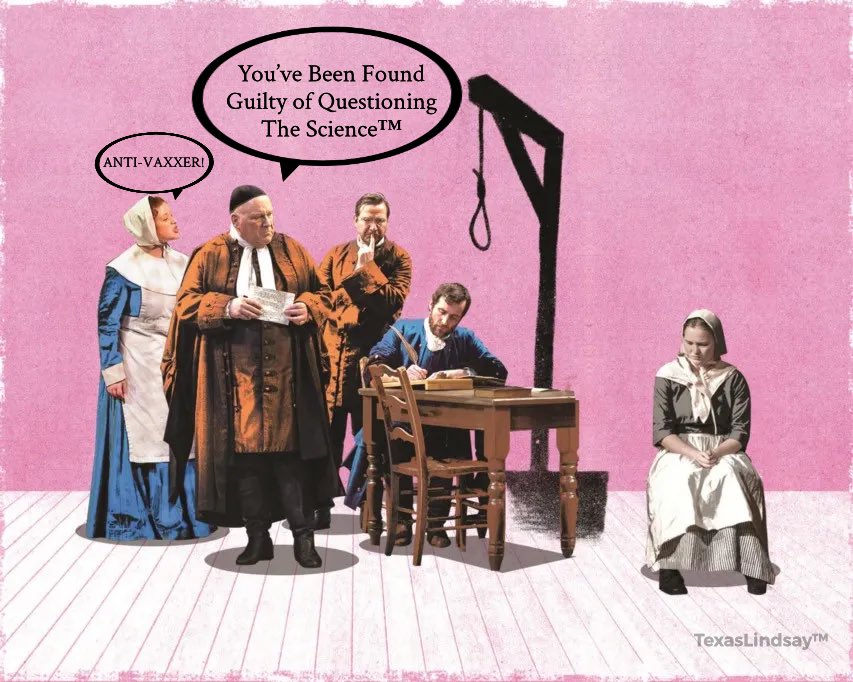

Content suppression techniques against dissent in the Fifth Estate - examples of COVID-19 censorship on social media

Written for researchers and others interested in the many methods available to suppress dissidents' digital voices. These techniques support contemporary censorship online, posing a digital visibility risk for dissidents challenging orthodox narratives in science.

The Fourth Estate emerged in the eighteenth century as the printing press enabled the rise of an independent press that could help check the power of governments, business, and industry. In similar ways, the internet supports a more independent collectivity of networked individuals, who contribute to a Fifth Estate (Dutton, 2023). This concept acknowledges how a network power shift results from individuals who can search, create, network, collaborate, and leak information in strategic ways. Such affordances can enhance individuals' informational and communicative power vis-à-vis other actors and institutions. A network power shift enables greater democratic accountability, whilst empowering networked agents in their everyday life and work. Digital platforms do enable online content creators to generate and share news that digital publics amplify via networked affordances (such as 💌 likes, " quotes " and sharing via # hashtag communities).

#1 Covering up algorithmic manipulation

Social media users who are not aware about censorship are unlikely to be upset about it (Jansen & Martin, 2015). Social media platforms have not been transparent about how they manipulated their recommender algorithms to provide higher visibility for the official COVID-19 narrative, or in crowding out original contributions from dissenters on social media timelines, and in search results. Such boosting ensured that dissent was seldom seen, or perceived as fringe minority's concern. As Dr Robert Malone tweeted, the computational algorithm-based method now 'supports the objectives of a Large Pharma- captured and politicised global public health enterprise'. Social media algorithms have come to serve a medical propaganda purpose that crafts and guides the 'public perception of scientific truths'. While algorithmic manipulation underpins most of the techniques listed below, it is concealed from social media platform users.

#2 Fact choke versus counter-narratives

An example she tweeted about was the BBC's Trusted New Initiative warning in 2019 about anti-vaxxers gaining traction across the internet, requiring algorithmic intervention to neutralise "anti-vaccine" content. In response, social media platforms were urged to flood users' screens with repetitive pro-(genetic)-vaccine messages normalising these experimental treatments. Simultaneously, messaging attacked alternate treatments that posed a threat to the vaccine agenda. Fact chokes also included 'warning screens' that were displayed before users could click on content flagged by "fact checkers" as "misinformation".

#3 Title-jacking

For the rare dissenting content that can achieve high viewership, another challenge is that title-jackers will leverage this popularity for very different outputs under exactly the same (or very similar) production titles. This makes it less easy for new viewers to find the original work. For example, Liz Crokin's 'Out of the Shadows’ documentary describes how Hollywood and the mainstream media manipulate audiences with propaganda. Since this documentary's release, several videos were published with the same title.

#4 Blacklisting trending dissent

Social media search engines typically allow their users to see what is currently the most popular content. In Twitter, dissenting hashtags and keywords that proved popular enough to feature amongst trending content, were quickly added to a 'trend blacklist' that hid unorthodox viewpoints. Tweets posted by accounts on this blacklist are prevented from trending regardless of how many likes or retweets they receive. On Twitter, Stanford Health Policy professor Jay Bhattacharya argues he was added to this blacklist for tweeting on a focused alternative to the indiscriminate COVID-19 lockdowns that many governments followed. In particular, The Great Barrington Declaration he wrote with Dr. Sunetra Gupta and Dr. Martin Kulldorff, which attracted over 940,000 supporting signatures.#5 Blacklisting content due to dodgy account interactions or external platform links

#6 Making content unlikeable and unsharable

This newsletter from Dr Steven Kirsch's (29.05.2024) described how a Rasmussen Reports video on YouTube had its 'like' button removed. As Figure 1 shows, users could only select a 'dislike' option. This button was restored for www.youtube.com/watch?v=NS_CapegoBA.

Figure 1. Youtube only offers dislike option for Rassmussen Reports video on Vaccine Deaths- sourced from Dr Steven Kirsch's newsletter (29.05.2024)

Social media platforms may also prevent resharing such content, or prohibit links to external websites that are not supported by these platforms' backends, or have been flagged for featuring inappropriate content.

#7 Disabling public commentary

#8 Making content unsearchable within, and across, digital platforms

#9 Rapid content takedowns

Social media companies could ask users to take down content that was in breach of COVID-19 "misinformation" policies, or automatically remove such content without its creators' consent. In 2021, META reported that it had removed more than 12 million pieces of content on COVID-19 and vaccines that global health experts had flagged as misinformation. YouTube has a medical misinformation policy that follows the World Health Organisation (WHO) and local health authorities guidance. In June 2021, YouTube removed a podcast in which the evidence of a reproductive hazard of mRNA shots was discussed between Dr Robert Malone and Steve Kirsch on Prof Bret Weinstein's DarkHorse channel. Teaching material that critiqued genetic vaccine efficacy data was automatically removed within seconds for going against its guidelines (see Shir Raz, Elisha, Martin, Ronnel, Guetzkow, 2022). The WHO reports that its guidance contributed to 850,000 videos related to harmful or misleading COVID-19 misinformation being removed from YouTube between February 2020 and January 2021.#10 Creating memory holes

#11 Rewriting history

#12 Concealing the motives behind censorship, and who its real enforcers are

|

| Figure 2. Global Public-Private Partnership (G3P) stakeholders - sourced from IainDavis.com (2021) article at https://unlimitedhangout.com/2021/12/investigative-reports/the-new-normal-the-civil-society-deception. |

Friday, 23 December 2022

A summary of 'Who is watching the World Health Organisation? ‘Post-truth’ moments beyond infodemic research'

A major criticism this paper raises is that infodemic research lacks earnest discussion on where health authorities’ own choices and guidelines might be contributing to ‘misinformation’, ‘disinformation’ and even ‘malinformation’. Rushed guidance based on weak evidence from international health organisations can perpetuate negative health and other societal outcomes, not ameliorate them! If health authorities’ choices are not up for review and debate, there is a danger that a hidden goal of the World Health Organisation (WHO) infodemic (or related disinfodemic funders’ research) could be to direct attention away from funders' multitude of failures in fighting pandemics with inappropriate guidelines and measures.

In The regime of ‘post-truth’: COVID-19 and the politics of knowledge (at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01596306.2021.1965544), Kwok, Singh and Heimans (2019) describe how the global health crisis of COVID-19 presents a fertile ground for exploring the complex division of knowledge labour in a ‘post-truth’ era. Kwok et al. (2019) illustrates this by describing COVID-19 knowledge production at university. Our paper focuses on the relationships between health communication, public health policy and recommended medical interventions.

Divisions of knowledge labour are described for (1) the ‘infodemic/disinfodemic research agenda’, (2) ‘mRNA vaccine research’ and (3) ‘personal health responsibility’. We argue for exploring intra- and inter relationships between influential knowledge development fields. In particular, the vaccine manufacturing pharmaceutical companies that drive and promote mRNA knowledge production. Within divisions of knowledge labour (1-3), we identify key inter-group contradictions between the interests of agencies and their contrasting goals. Such conflicts are useful to consider in relation to potential gaps in the WHO’s infodemic research agenda:

For (1), a key contradiction is that infodemic scholars benefit from health authority funding may face difficulties questioning their “scientific” guidance. We flag how the WHO ’s advice for managing COVID-19 departed markedly from a 2019 review of evidence it commissioned (see https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35444988).

(2)’s division features very different contradictions. Notably, the pivotal role that pharmaceutical companies have in generating vaccine discourse is massively conflicted. Conflict of interest arises in pursuing costly research on novel mRNA vaccines because whether the company producing these therapies will ultimately benefit financially from the future sales of these therapies depends entirely on the published efficacy and safety results from their own research. The division of knowledge labour for (2) mRNA vaccine development should not be considered separately from COVID-19’s in Higher Education or the (1) infodemic research agenda. Multinational pharmaceutical companies direct the research agenda in academia and medical research discourse through the lucrative grants they distribute. Research organisations dependant on external funding for covering budget shortfalls will be more susceptible to the influence of those funders on their research programs.

However, from the perspective of orthodoxy, views that support new paradigms are unverified knowledge (and potentially "misinformation"). Any international health organisation that wishes to be an evaluator must have the scientific expertise for managing this ongoing ‘paradox’, or irresolvable contradiction. Organisations such as the WHO may theoretically be able to convene such knowledge, but their dependency on funding from conflicted parties would normally render them ineligible to perform such a task. This is particularly salient where powerful agents can collaborate across divisions of knowledge labour for establishing an institutional oligarchy. Such hegemonic collaboration can suppress alternative viewpoints that contest and query powerful agents’ interests.

Our article results from collaboration between The Noakes Foundation and PANDA. The authors thank JTSA’s editors for the opportunity to contribute to its special issue, the paper’s critical reviewers for their helpful suggestions and AOSIS for editing and proof-reading the paper.

This is the third publication from The Noakes Foundation’s Academic Free Speech and Digital Voices (AFSDV) project. Do follow me on Twitter or https://www.researchgate.net/project/Academic-Free-Speech-and-Digital-Voices-AFSDV for updates regarding it.

I welcome you sharing constructive comments, below.

orcid.org/0000-0001-9566-8983

orcid.org/0000-0001-9566-8983