Friday, 23 December 2022

A summary of 'Who is watching the World Health Organisation? ‘Post-truth’ moments beyond infodemic research'

A major criticism this paper raises is that infodemic research lacks earnest discussion on where health authorities’ own choices and guidelines might be contributing to ‘misinformation’, ‘disinformation’ and even ‘malinformation’. Rushed guidance based on weak evidence from international health organisations can perpetuate negative health and other societal outcomes, not ameliorate them! If health authorities’ choices are not up for review and debate, there is a danger that a hidden goal of the World Health Organisation (WHO) infodemic (or related disinfodemic funders’ research) could be to direct attention away from funders' multitude of failures in fighting pandemics with inappropriate guidelines and measures.

In The regime of ‘post-truth’: COVID-19 and the politics of knowledge (at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01596306.2021.1965544), Kwok, Singh and Heimans (2019) describe how the global health crisis of COVID-19 presents a fertile ground for exploring the complex division of knowledge labour in a ‘post-truth’ era. Kwok et al. (2019) illustrates this by describing COVID-19 knowledge production at university. Our paper focuses on the relationships between health communication, public health policy and recommended medical interventions.

Divisions of knowledge labour are described for (1) the ‘infodemic/disinfodemic research agenda’, (2) ‘mRNA vaccine research’ and (3) ‘personal health responsibility’. We argue for exploring intra- and inter relationships between influential knowledge development fields. In particular, the vaccine manufacturing pharmaceutical companies that drive and promote mRNA knowledge production. Within divisions of knowledge labour (1-3), we identify key inter-group contradictions between the interests of agencies and their contrasting goals. Such conflicts are useful to consider in relation to potential gaps in the WHO’s infodemic research agenda:

For (1), a key contradiction is that infodemic scholars benefit from health authority funding may face difficulties questioning their “scientific” guidance. We flag how the WHO ’s advice for managing COVID-19 departed markedly from a 2019 review of evidence it commissioned (see https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35444988).

(2)’s division features very different contradictions. Notably, the pivotal role that pharmaceutical companies have in generating vaccine discourse is massively conflicted. Conflict of interest arises in pursuing costly research on novel mRNA vaccines because whether the company producing these therapies will ultimately benefit financially from the future sales of these therapies depends entirely on the published efficacy and safety results from their own research. The division of knowledge labour for (2) mRNA vaccine development should not be considered separately from COVID-19’s in Higher Education or the (1) infodemic research agenda. Multinational pharmaceutical companies direct the research agenda in academia and medical research discourse through the lucrative grants they distribute. Research organisations dependant on external funding for covering budget shortfalls will be more susceptible to the influence of those funders on their research programs.

However, from the perspective of orthodoxy, views that support new paradigms are unverified knowledge (and potentially "misinformation"). Any international health organisation that wishes to be an evaluator must have the scientific expertise for managing this ongoing ‘paradox’, or irresolvable contradiction. Organisations such as the WHO may theoretically be able to convene such knowledge, but their dependency on funding from conflicted parties would normally render them ineligible to perform such a task. This is particularly salient where powerful agents can collaborate across divisions of knowledge labour for establishing an institutional oligarchy. Such hegemonic collaboration can suppress alternative viewpoints that contest and query powerful agents’ interests.

Our article results from collaboration between The Noakes Foundation and PANDA. The authors thank JTSA’s editors for the opportunity to contribute to its special issue, the paper’s critical reviewers for their helpful suggestions and AOSIS for editing and proof-reading the paper.

This is the third publication from The Noakes Foundation’s Academic Free Speech and Digital Voices (AFSDV) project. Do follow me on Twitter or https://www.researchgate.net/project/Academic-Free-Speech-and-Digital-Voices-AFSDV for updates regarding it.

I welcome you sharing constructive comments, below.

Monday, 29 August 2022

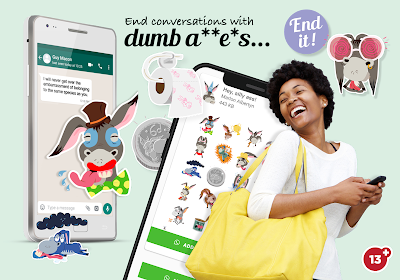

Banner design changes for Google Play Store's approval of the Shushmoji app

In submitting the Shushmoji app to the Google Play store, several changes were required to the app's promotional banners before Google Play approved the app. The changes that Create With Cape Town made may be of interest to other designers preparing edgy campaigns, given Google Play Store's somewhat opaque feedback- the store simply flags which designs are rejected, but does not specify exactly which elements must change.

Below is a Slideshare presentation featuring the varying banner iterations - see if you can spot the differences? The answers follow below...

The first major change was adding a 13+ graphic in the bottom right of the presentation to comply with the policy that ‘app’s marketing imagery and text must make it clear that the app is only for young people aged 13 or older’. Subsequently, the Google Play Store calculated this rating for each country based on its app questionnaire. It decided on to a revised age restriction of 12+, so this banner is not inaccurate but will be updated with the next app version's submission.

So, the banner's title was changed to 'End conversations with silly donkeys'. The WhatsApp screen graphics were also changed- the 'silly ass' part of 'Hey, silly ass' sticker set was blurred to make it obvious that the banner title is "censored". Lastly, in the left’s WhatsApp exchange ’the same species as you’ was changed to simply ‘humanity’. Out of an excess of caution, End it! was changed to End the chat! We did not want our AI Google overlord's algorithm to misinterpret 'End it!' as telling someone to end their life.

All the changes above proved sufficient to meet the Google Play Store's approval of the Shushmoji app.

Friday, 26 August 2022

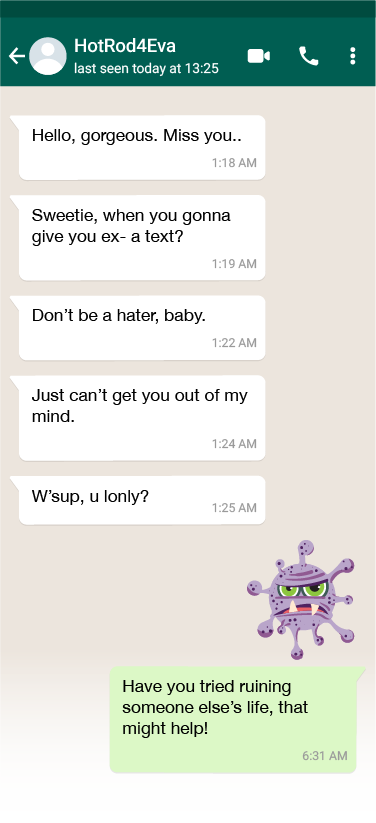

Want emoji stickers to end #WhatsApp chats with #cyberbullies? The #Shushmoji app on #Android is here!

Saturday, 23 April 2022

Eight conceptual challenges in developing the 'online academic bullying' framework

1 NEW FORMS OF POWER IMBALANCE

|

| Figure 1. Faculties and departments in which employees persistently criticised the Emeritus Professor on social media (Travis Noakes, 2020) |

Attacking a scientific dissident as a pre-defined target seemed to provide attackers with an instant form of credibility- they did not have to prove their symbolic credentials to gain visibility. Few of the professor's blogging critics were Health Science scholars. Despite making no scholarly contribution to the debate, some academic cyberbullies seemed to achieve visibility as opinion "leaders" online. This shows how micro-celebrity hijacking can apply for Higher Education (HE) employees. Academic bloggers criticise public intellectuals for "wrongthink" thereby gaining attentional capital- blogged critiques by "independent" critical thinkers can convert into appearances on broadcast media.

Another dimension of power imbalance may lie in technical cultural capital- an OAB recipient who has less knowledge of the digital platform(s) on which she is being attacked may be at a serious disadvantage. For example, cyberbullies can use advantages in their ‘digital dimensions’ (Paino & Renzulli, 2013) of cultural capital for gaining greater visibility. They can leverage a myriad of online presences for amplifying their attacks, whilst leveraging multiple chains of digital publication that are difficult for a victim to reply to.

This suggests another imbalance whereby OAB recipients will struggle to defend themselves against asymmetrical cyber-critiques. It may be exhausting to respond to frequent criticisms, across a myriad of digital platforms and conflicting timezones.

2 BEYOND TROLLS: ACADEMIC CYBERBULLIES AS DECEIVERS, FLAMERS, ETC.

3 SCIENTIFIC SUPPRESSION VERSUS BIO-MEDICAL HERESY "JUSTIFIES" HARASSMENT

4 FOREGROUNDING THE VICTIM’S PERSPECTIVE

In university workplaces, bullies can use a justification of “academic freedom” to condone actions that would be unacceptable in other workplaces (Driver, 2018). For example, an academic lecturer (who is neither a scholar nor a scientist) published thirty blog posts that criticised the Emeritus Professor's popularisation of LCHF science. Although by no means an academic peer, this junior lecturer might justify such fervent criticism of a fellow employee at the same university as a necessary part of academic freedom in an institute of higher learning. Nevertheless, such obsessive behaviour from a low-ranking, under-qualified employee seems unlikely to be acceptable at any other place of employment.

6 GUARDIANS AGAINST VICTIMS OF ACADEMIC BULLYING

8 A COMPLEX FORM FOR AN EXTREME CASE

GRAPHIC CREDITS

Stop, academic bully! shushmoji™ graphics courtesy of Create With Cape Town.

Thursday, 14 April 2022

Behind 'Design principles for developing critique and academic argument in a blended-learning data visualization course'

Our new chapter is a sequel to 'Exploring academic argument in information graphics' (2020), in which we proposed the framework for argument in data visualizations shown in Table 1. This social semiotic framework provides a holistic view that is useful for providing feedback and recognising students’ work as realised through the ideational, interpersonal, and textual meta-functions. For example, in addition to the verbal (written) mode that they are usually assessed on in Higher Education, students' digital poster designs must also consider composition, size, shape and colour choices.

Designed by Arlene Archer and Travis Noakes, 2021.

1) Delimiting the scope of the task

2) Encouraging the use of readily accessible design tools

3) Considering gains and losses in digital translations

4) Implementing a process approach for developing argument and encouraging reflection

5) Developing meta-languages of critique and argument

6) Acknowledging different audiences and the risks of sharing work as novices

"Tumi" and "Mark" followed different approaches to metalevel critique in their data visualization project's. Tumi’s presentation (see Figures 1 and 2) critiqued the usefulness of Youth Explorer for exploring education in a peripheral township community versus a suburban ‘core community’. In contrasting the Langa township ward's educational attendance data versus the leafy suburb of Pinelands, she flagged why the results may be skewed unfavourably against Langa- children from peripheral communities often travel to core communities for schooling, so data for both core and peripheral communities “can be blurred to some extent”. Tumi also flagged that youth accused of contact crime were not necessarily ‘convicted or found guilty’.

By contrast, Mark’s poster (see Figure 3) critiqued the statistics available for understanding ‘poor grade 8 systemic results’ and the reasons for higher drop-out rates in schooling between suburbs. His poster explored the limitations of what Youth Explorer can tell us about systemic tests and how these link to dropout rates and final year pass rates. He argued that a shortcoming is the dataset’s failure to convey 'the role that extra-curricular support plays' in shaping learners’ results. Mark's poster reflected the fact that many children from affluent homes go for extra lessons after school to improve subject results. This knowledge of concerted cultivation was based on his personal experience, but is unaccounted for in most official accounts of educational input.

Both cases reveal how teaching a social semiotic approach for analysing and producing argument proved helpful. It informed changes to a data visualisation poster course that could better support students’ development as critical designers and engaged citizens- the two aspirant media professionals' meta-critiques flagged important challenges in relying on data that may be incorrect and incomplete, accurately spotlighting the inherent difficulties of simplifying qualitative complexity into numbers for their audiences.

If you would like to view a presentation on our research, please visit my earlier blog post at

https://www.travisnoakes.co.za/2021/10/the-presentation-developing-critique.html.

The research is based upon work supported by the British Academy Newton Advanced Fellowship scheme. Travis’ research was supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship (2019-21) at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology. Both authors thank the University of Cape Town’s Centre for Film and Media Studies for facilitating our research with students between 2017 and 2018. In particular, we thank Professor Marion Walton and Dr Martha Evans for their valued assistance. We also greatly appreciate the feedback from the editors and reviewers at Learning Design Voices.

Need support doing Social Semiotic research in Africa?

Both Arlene and Travis are members of the South African Multimodality in Education research group (SAME) hosted by UCT. Should you be interested in sharing your multimodal research project with its experts, please contact SAME.

orcid.org/0000-0001-9566-8983

orcid.org/0000-0001-9566-8983